All articles with images are easily accessible at: sergeplantureux.blog

Catégorie : Non classé (Page 1 of 2)

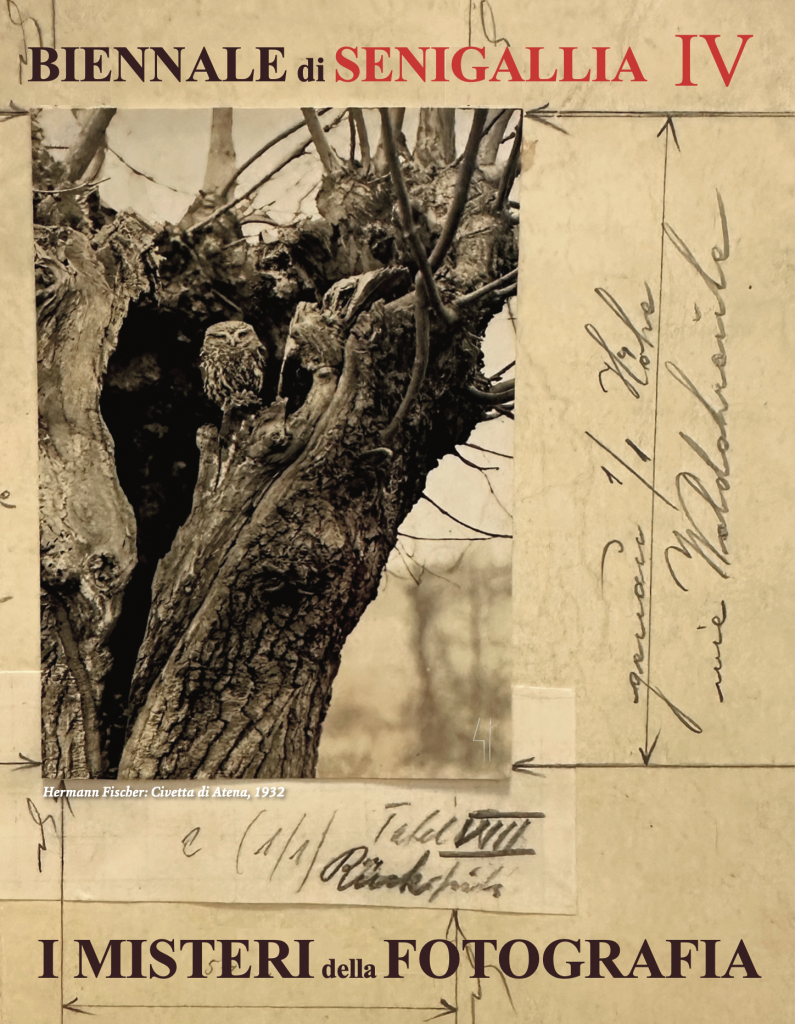

Siamo felici di annunciare una grande festa di musica, luce e fotografia per la prossima Biennale di Senigallia, dal 19 al 22 giugno 2026.

La fiera dei collezionisti, la conferenza e gli incontri con gli artisti si svolgeranno proprio nel weekend della Festa della Musica e del solstizio d’estate, creando un’occasione unica per celebrare arte, natura e creatività.

L’evento è organizzato in collaborazione con il Comune di Senigallia nell’ambito del progetto “Senigallia Città della Fotografia”.

A giugno le giornate sono splendide e la spiaggia invita a rilassarsi. Le tre conferenze sono previste nel tardo pomeriggio.

ARRIVO A SENIGALLIA – MERCOLEDÌ 18 GIUGNO

I primi partecipanti, docenti e visitatori, saranno accolti nella serata di mercoledì 18 giugno con un piccolo buffet e una visita guidata della mostra di dipinti e fotografie di Alfonso Napolitano, in omaggio a Mario Giacomelli, nel centenario della sua nascita.

Ritrovo a partire dalle ore 18:30 in via Fratelli Bandiera 64.

PRIMO GIORNO – GIOVEDÌ 19 GIUGNO

Mattinata. Passeggiata al mercato settimanale e sport acquatici.

11:00: Palazzo Mastai – Visita alla casa natale di Papa Pio IX. Mostra speciale di dagherrotipi: “È forse questa la prima fotografia mai scattata a Senigallia?”

Tardo pomeriggio – Palazzetto Baviera

17:00: Visita guidata della mostra. Arthur Rimbaud e la fotografia

18:00: Conferenza – Rimbaud e la fotografia. • Le fotografie che rappresentano Arthur Rimbaud • E Arthur Rimbaud che prende in considerazione l’idea di diventare fotografo.

Intervengono:

• André Guyaux (Collège de France, conosce Rimbaud come le sue tasche)

• Hugues Fontaine (autore e curatore)

• Jean-Hugues Berrou (fotografo, regista, co-autore)

• Serge Plantureux (Atelier 41, Senigallia)

André Guyaux parlerà dello straordinario destino di un piccolo ritratto, la carte de visite realizzata da Carjat, divenuta ispirazione per centinaia di artisti e una delle immagini più rappresentate nella cultura generale.

Hugues Fontaine parlerà dell’attività di Arthur Rimbaud nella regione del Mar Rosso e delle tracce fotografiche che vi ha lasciato, soffermandosi in particolare su una recente scoperta che lo appassiona: qui Rimbaud riappare come un fantasma in una fotografia recentemente ritrovata, scattata da uno degli esploratori o viaggiatori della zona.

Jean-Hugues Berrou ci racconterà della sua esperienza, avendo creato l’iconografia di tre libri su Arthur Rimbaud.

Infine, Serge Plantureux illustrerà la sua indagine su un ritratto recentemente emerso che potrebbe essere proprio un ritratto del poeta di passaggio a Vienna, capitale dell’Austria.

Sera – Rotonda a Mare

21:00: Concerto – Maurizio Barbetti interpreta “Music for Airports” di Brian Eno e “Requie(m)”, dedicato a Giorgio Cutini.

22:00: Proiezione dei film di Jean-Hugues Berrou dedicati a Rimbaud: “Praline” (52 min), “Ogaden” (28 min).

SECONDO GIORNO – VENERDÌ 20 GIUGNO

Mattina in città

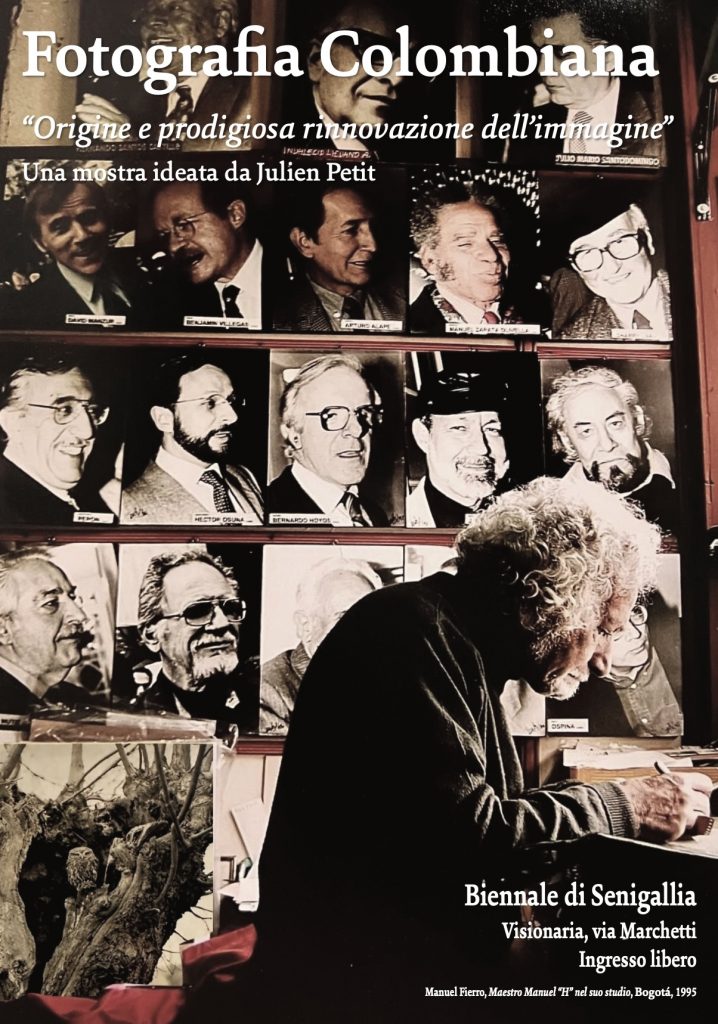

11:00 Degustazione del caffé della Sierra Macarena, al Bar di Piazza Saffi. A seguire: Visita guidata alla Visionaria della Mostra Fotografia colombiana, A cura di Julien Petit con gli studenti Erasmus

17:00: Visita guidata della mostra – L’invenzione della fotografia

18:00: I misteri dell’invenzione della fotografia: dagli esperimenti di Niépce del 1825 ai 200 anni della scoperta.

Intervengono:

• Pierre-Yves Mahé (Casa-Museo Niépce)

• Serge Plantureux, Alphonse-Eugène Hubert, l’inventore sconosciuto

• Jean Dhombres (già Università di Nantes, storia della scienza)

• Julien Petit (curatore, Bogotá, attualmente INHA/Sorbonne)

• Maria Francesca Bonetti (SISF, Roma)

Sera – Foro Annorario

20:00–22:00: Inaugurazione VIP della fiera all’Ex-Pescheria.

Sera – Palazzetto Baviera & Palazzo del Duca

21:00: Conferenza – Collezione Donata Pizzi con Silvia Camporesi

A seguire: Visita guidata al Palazzo del Duca

TERZO GIORNO – SABATO 21 GIUGNO

Mattina – Foro Annonario – Art Fair

08:00–14:00: Fiera all’Ex-Pescheria. Non fate tardi!

Tardo pomeriggio – Palazzetto Baviera

17:00: Workshop sulle antiche tecniche – Alberto Polonara, Massimo Marchini, Ambrotipo con Michael Kolster

17:00: Associazione Bellanca, Via Marchetti 47 – “Divento”, Simona Ballesio

Tardo pomeriggio – Rocca Roveresca – Musica e Fotografia

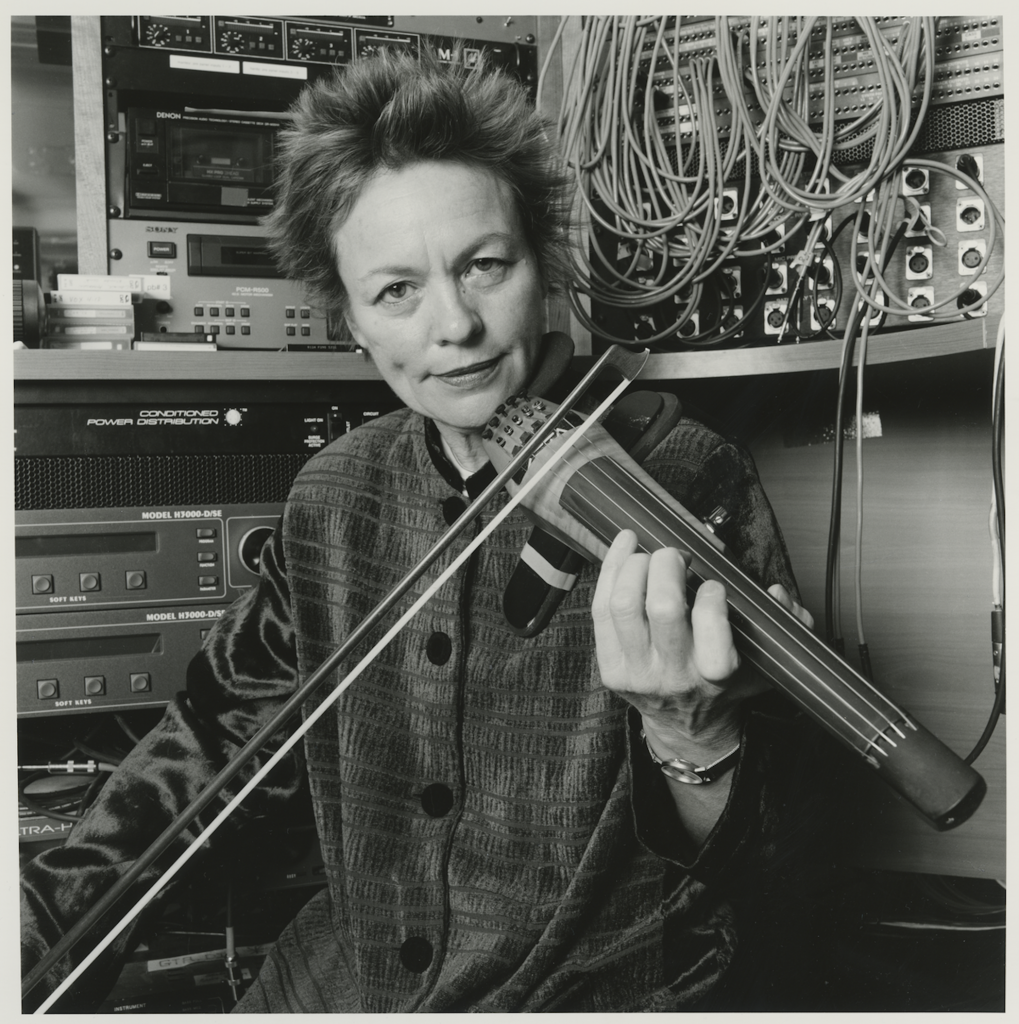

17:30: Visita guidata della mostra – Ritratti di musicisti di Nancy Katz

18:00: Conferenza – Il Pantheon di Nancy Katz. Relatore: Michael Sachs

19:00: Concerto-aperitivo, Ballo in maschera (ingresso gratuito, ma prenotate: fotografia@atelier41.org)

21:00: Buffet al Lapsus Space (Giardini della Rocca, ex-Elettrauto) – Mostra “La Finestra dell’Invenzione, Riflessioni irregolari”

QUARTO GIORNO – DOMENICA 22 GIUGNO

Mattina – Portici Ercolani

Dalle 9:00: Mercatino delle pulci mensile. Occasioni da non perdere!

Giornata al mare

Tardo pomeriggio & sera – Rotonda a Mare

18:00: Conferenza su Niépce e l’invenzione della fotografia

• Daniel Girardin (ex-Musée de l’Elysée)

• Cristina Panicali con Agathe Pruvost. Presentazione delle ricerche di Elizabeth Fulhame sui sali d’argento, 1794)

• Michael Kolster, Boyden College, Brunswick, Maine. About the wet plate photographic process, invented in 1850 and predominate until the 1880s.

21:00: Conferenza su Mario Giacomelli

• Lorenzo Cicconi Massi, fotografo e regista

• Simone Giacomelli, Archivio Giacomelli

• Mauro Pierfederici, attore

Film – Lorenzo Cicconi Massi, “Mi Ricordo Mario Giacomelli”

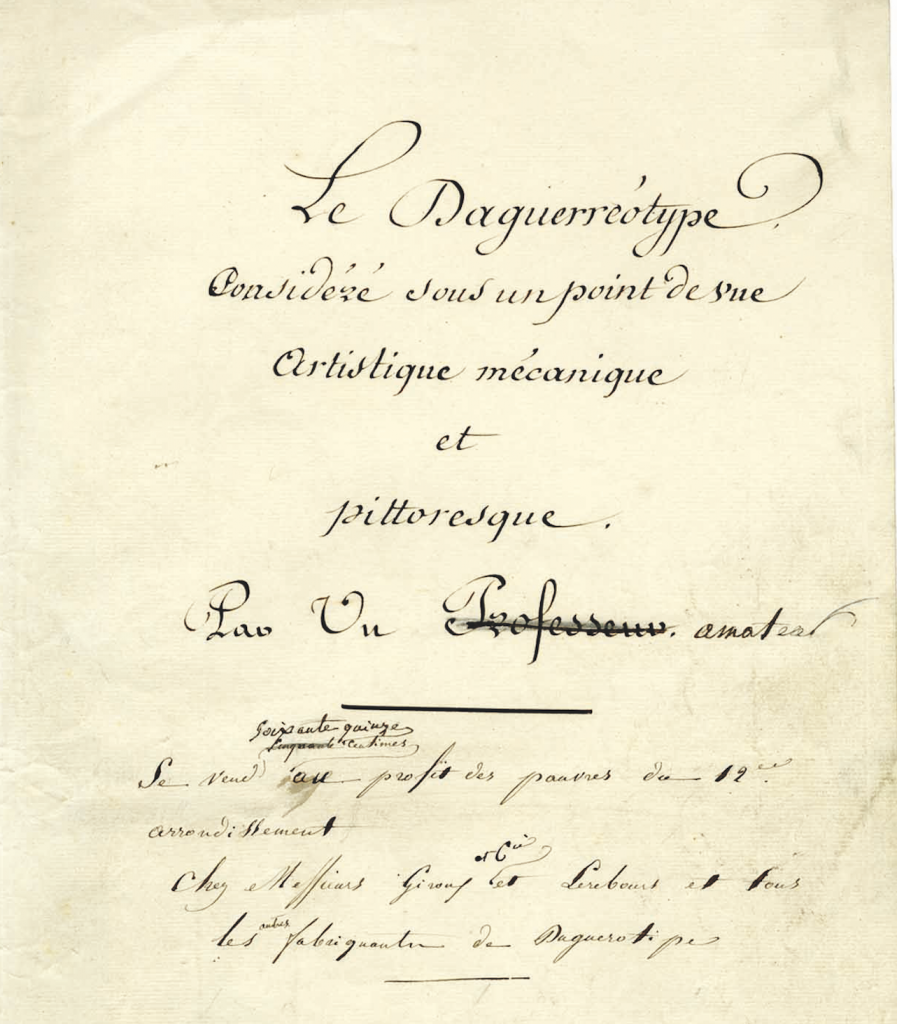

Curiosità storica:

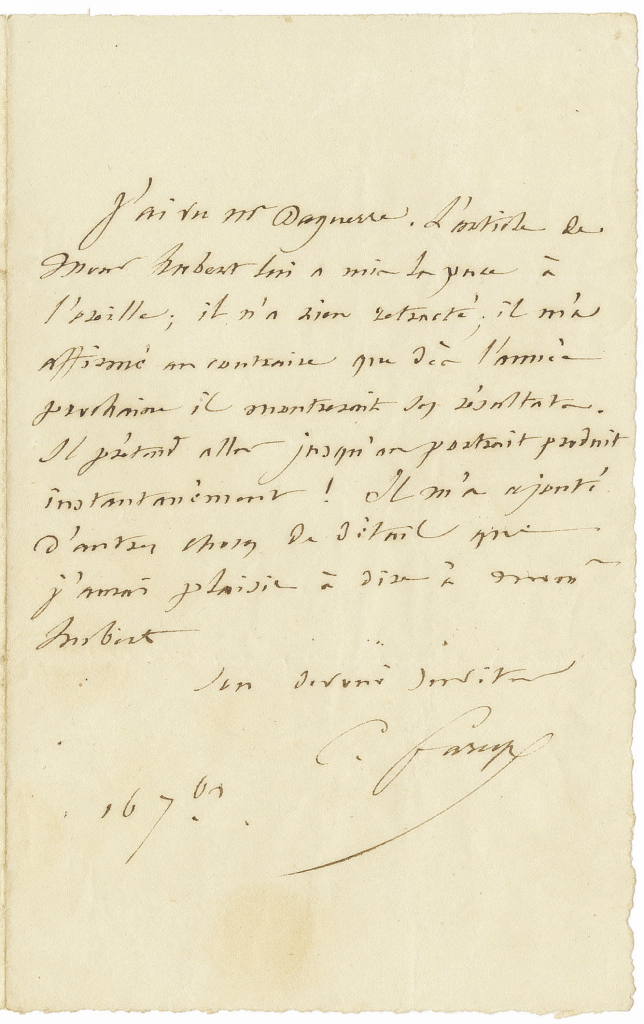

« J’ai vu Mr Daguerre. L’article de Mr Hubert lui a mis la puce à l’oreille ; il n’a rien rétracté ; il m’a affirmé au contraire que dès l’année prochaine il montrerait ses résultats. Il prétend aller jusqu’au portrait produit instantanément! Il m’a ajouté d’autres choses de détail que j’aurai plaisir à dire à Mr Hubert. Son dévoué serviteur, Charles Farcy, 16 7bre » (16 septembre 1836)

«Ho visto il signor Daguerre. L’articolo del signor Hubert gli ha fatto venire qualche sospetto; non ha ritrattato nulla; anzi, mi ha assicurato che già l’anno prossimo mostrerà i suoi risultati. Sostiene di arrivare fino al ritratto prodotto istantaneamente! Mi ha aggiunto altri dettagli che avrò piacere di riferire al signor Hubert. Il suo devoto servitore, Charles Farcy, 16 settembre 1836»

Charles François Farcy (1792–1867) fu critico d’arte e fondatore del Journal des Artistes nel 1827, che diresse fino al 1841. Pubblicò l’articolo di Hubert, con cui aveva un rapporto editore-autore. Si fa riferimento all’articolo pubblicato da M. Hubert nel Journal des artistes dell’11 settembre 1836 “M. Daguerre, la camera oscura e i disegni che si fanno da soli”.

Da vedere al Palazzetto Baviera, piano superiore

LE MOSTRE

Palazzetto Baviera (da giovedì a domenica 17-23)

Biglietteria online www.liveticket.com

I misteri della Fotografia I : I misteri dell’invenzione

- Chi siete Signor’Daguerre ?

- Niépce, il vero inventore della Fotografia

- Alphonse-Eugène Hubert, l’inventore sconosciuto

- Il contributo di altri pionieri come Talbot, Bayard, Morse

I misteri della Fotografia II

- Immagini di Roma 1853-1866 Presentazione de stampe inedite Leptographiche di Aguado e Coulon, Roma (1853-1866).

- Keichi Tahara, Finestra, 1973-1977.

- Omaggio a Niepce, fotografi contemporanei, Contributi di Michael Kolster (Boyden College, Maine, USA) sui ambrotipi. Massimo Marchini (Senigallia) e Simona Ballesio.

- Il Pantheon di Nancy Katz, 24 ritratti di fotografi ed artisti.

- Ricostruzione della « Table servie » di Niepce e Nature Morte, incisioni di Morandi

I misteri della Fotografia III

- Arthur Rimbaud e la fotografia, ritratti del Poeta, progetto di studio fotografico in Etiopia (1880-1885).

- Focus su un capitolo della fotografia in Africa, Studi in Africa occidentale, 1960-1980.

Palazzo del Duca (da giovedì a domenica 17-23)

Biglietteria online www.liveticket.com

Mise en Scène – immagini e libri dalla Collezione Donata Pizzi, a cura di Luca Panaro

Il Realismo Magico Di Mario Giacomelli, a cura di Katiuscia Biondi

Visionaria

Fotografia colombiana, A cura di Julien Petit con gli studenti Erasmus l’Università Politecnica des Hautes-de-France-Valenciennes. (ingresso libero)

Palazzo Mastai (dal lunedì al sabato 9-12/16-18) Via Mastai

Senigallia d’argento. Quella che potrebbe essere la prima fotografia scattata a Senigallia e alcuni dagherrotipi italiani.

LE MOSTRE IN CITTA’

Ingresso libero

Associazione Augusto Bellanca

Via Marchetti, 47

Divento

Fotografie di Simona Ballesio, tecniche antiche artigianale.

Bandiera 64

Via Fratelli Bandiera 64

Omaggio a Mario Giacomelli

Mostra curata da Patrizia Loconte e Alfonso Napolitano.

Box/3

Maurizio Cesarini

Mostra curata da Paola Casagrande.

Lapsus

Giardini della Rocca (ex-elettrauto)

La Finestra dell’inventore, mostra sulle condizione di maturazione di un’idea, con un opera originale di Désirée Hellé

Niente di Nuovo

Via Testaferrata 4

Mostra di vetri muranesi antichi

MOSTRE MERCATO

Ingresso libero

SABATO 21 GIUGNO

Ore 8-14 Ex-Pescheria

Fiera di Fotografia

Mostra mercato di fotografia antica e moderna.

DOMENICA 22 GIUGNO

Ore 10-18 Portici Ercolani

Antiquariato alla Vecchia Filanda

Mostra mercato di antiquariato, collezionismo e modernariato.

I LABORATORI

SABATO 21 GIUGNO

Ore 17-23 Palazzetto Baviera

Workshop sulle antiche tecniche di stampa a cura di Artline

Workshop sugli ambrotipi a cura di Michael Kloster

Un momento di approfondimento teorico e pratico delle antiche tecniche di stampa fotografica.

Ingresso libero

DOMENICA 22 GIUGNO

ORE 21 VISIONARIA

Uno sguardo oltre la finestra

Laboratorio creativo per bambini e adulti a cura di Lapsus. Solo su prenotazione ass.lapsus@gmail.com

Ingresso libero

Le date della Biennale di Senigallia 2025 sono state appena cambiate.

Mentre i giorni iniziano lentamente ad allungarsi e la Terra continua la sua orbita annuale intorno al Sole, siamo lieti di annunciare una grande celebrazione della musica, della luce e della fotografia per la prossima Biennale di Senigallia.

L’amministrazione comunale, insieme ai partner della Biennale, ha proposto di spostare l’evento verso la bella stagione per permettere ai visitatori di godere pienamente della spiaggia e delle attività marine.

La fiera dei collezionisti, la conferenza e gli incontri con gli artisti si svolgeranno durante il fine settimana della Festa della Musica e del solstizio d’estate, creando un momento unico per celebrare l’arte, la natura e la creatività.

Segnate le date nei vostri calendari: 19, 20 e 21 giugno 2025, e unitevi a noi a Senigallia e nel mondo sensibile per questa modesta occasione in cui musica, luce e fotografia si uniranno per onorare i ritmi senza tempo dei corpi celesti e le arti più pacifiche dell’umanità.

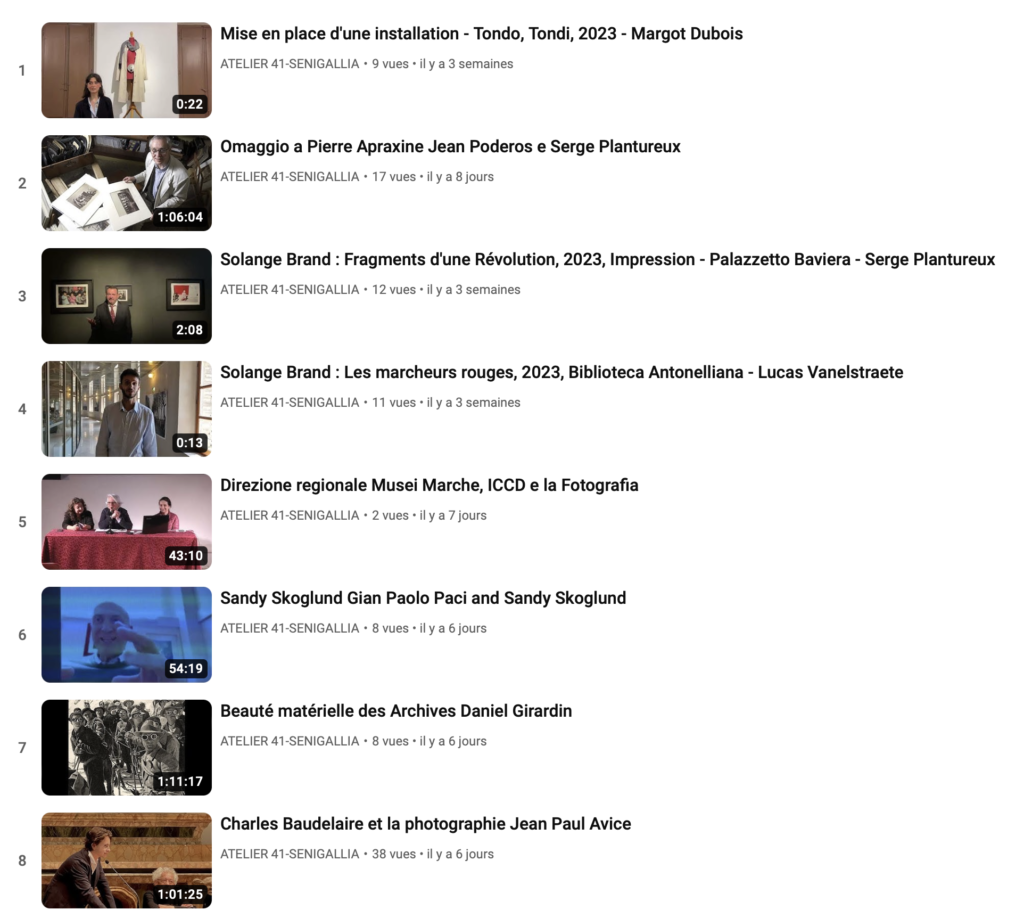

We are pleased to announce that a selection of our conferences and exhibition tours, curated with great care for the 3rd Senigallia Biennale, is now available on YouTube

Dear distinguished listeners,

We are pleased to announce that a selection of our conferences and exhibition tours, curated with great care for the 3rd Senigallia Biennale, is now available on YouTube.

This exciting development allows you to delve into these moments, sharing them with a wider audience and those unable to attend due to unforeseen circumstances.

Please bear with us as we share a minor detail: the conferences were initially conducted in French and Italian. However, we are diligently working to provide English subtitles through the use of artificial intelligence. We understand the challenges that lie ahead, but our unwavering commitment drives us to improve the accessibility and reach of our cultural programs.

We sincerely appreciate your unwavering support and dedication to the Senigallia Biennale.

Photographically yours,

Thursday 18 May / Jeudi 18 mai 2023 – 9:15

Enzo Carli, Gemmy Tarini, conferenza in italiano, con sotto-titoli in italiano. Tarini è stato uno dei principali fotografi senigalliesi insieme a Giuseppe Cavalli e Mario Carafoli. Tarini, in particolare, ha avuto un ruolo fondamentale nella ricerca fotografica, collaborando con Cavalli e partecipando alle mostre e ai concorsi fotografici dell’epoca.

Link to the Italian conference video : https://youtu.be/W7wFtupzjCw

Thursday 18 May / Jeudi 18 mai 2023 – 9:15

Daniel Girardin, La Beauté matériel des archives. Un cas d’étude, les archives Hans Steiner, écriture et réalisation d’un film pour le Musée de l’Élysée, Lausanne

La conférence de Daniel Girardin portait sur le thème de la beauté des archives, en se concentrant sur la vie, la mort et le destin des images. Il a souligné l’importance de la sélection opérée par les photographes dans la constitution de leurs archives, ainsi que la question de la collection et de l’archive en général. Daniel a comparé les archives photographiques aux archives textuelles, mettant en évidence la valeur documentaire et émotionnelle des photographies. Il a abordé les analyses de Jacques Derrida sur le pouvoir des archives, l’angoisse et la nostalgie suscitées par les photographies, ainsi que la question de la vérité au sein des archives. Un exemple concret a été présenté, celui du fond photographique de Hans Steiner, un photographe suisse. Daniel a décrit les défis rencontrés avec ce fond, notamment l’absence de références temporelles, spatiales et nominatives.

Lien d’accès à la vidéo de la conférence : https://youtu.be/gUP7YFMNQ28

Accès au film mis en ligne par l’Université de Lausanne “Hans Steiner, un destin de photographe”: https://youtu.be/e0HUpZB-OYc

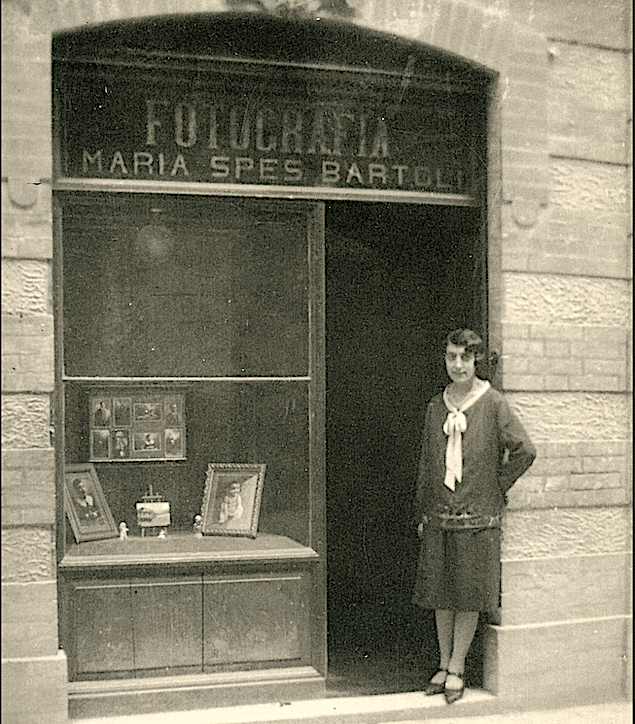

Friday 19 May / Vendredi 18 mai 2023 – 17:15

Maria Spes Bartoli. Conferenza di Simona Guerra in italiano con sotto-titoli in italiano

Maria Spes Bartoli è stata una fotografa italiana nata a Senigallia nel 1888. La sua carriera e la sua eredità sono notevoli, in quanto fu la prima donna fotografa in Italia a possedere uno studio proprio, cosa eccezionale per l’epoca. Nonostante le difficoltà incontrate, soprattutto durante la guerra, quando dovette gestire due studi in assenza del padre e del fratello mobilitati, Maria Spes sviluppò le sue capacità artistiche e il suo impegno nella fotografia.

Lien d’accès à la vidéo de la conférence : https://youtu.be/12AIoPVmQ3g

There are a total of 23 videos, visit of exhibitions and making-of of the Biennale on You-tube : Playlist IIIb III BIENNALE DI SENIGALLIA

Le riprese video sono state effettuate con il supporto dell’emittente televisiva locale Senigallia Notizie, del cameraman Alberto Olivieri.

La BIENNALE DI SENIGALLIA si inserisce nell’ambito del progetto Senigallia Città della Fotografia, promosso dalla Regione Marche e realizzato dal Comune di Senigallia e da Atelier 41 in collaborazione con la Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Jesi.

The video is online, here’s the French text and an English translation

La video est en ligne, en voici le texte et une traduction en anglais

Bienvenue à tous, merci d’être venus. Nous sommes aujourd’hui le 19 mai 2023, c’est le second jour des rencontres dans le cadre de la 3e Biennale de photographie sénégalaise. Actuellement, il est 18h15 et nous sommes dans la rotonde au bord de la mer. Je vais passer la parole à Jean Poderos.

Jean Poderos est éditeur, plus précisément éditeur de livres pour enfants et de beaux livres. Il a publié plus de 250 livres dans sa maison d’édition, qui s’appelle Éditions Courtes et Longues. Par exemple, il a publié un livre sur Hugo Pratt et un livre sur le photographe Thiollier en collaboration avec le Musée d’Orsay lors d’une exposition.

Maintenant, je passe la parole à Jean. Merci Serge et bonsoir à toutes et à tous. Serge l’a fait donc, je ne vais pas me présenter, mais je ne vais pas non plus vous présenter Pierre Apraxine, dont je vais vous parler maintenant pendant un certain nombre de minutes et qui va se dévoiler à vous petit à petit. Pour ceux ou celles qui ne le connaissent pas, je peux vous dire que l’histoire de Pierre, mon histoire avec Pierre, c’est l’histoire d’une rencontre qui ne s’est pas faite en 2000. Il organisait au Musée d’Orsay une exposition sur la Castiglione et Jean-Michel Ottoniel, l’artiste Ottoniel, qui est un ami, m’a appelé et m’a dit que je travaillais à l’époque pour vos magazines, j’étais journaliste, donc, et il m’a dit : « Viens, il y a cette exposition, ce sera intéressant que tu rencontres Pierre Apraxine. » Bon, les choses de la vie sont parfois mal faites, je ne suis pas allé voir Pierre Apraxine, je ne suis pas allé voir non plus l’exposition de la Castiglione. Je n’ai pas vu cette exposition, c’est un grand regret aujourd’hui, mais c’est comme ça. Et puis, Pierre, je l’ai rencontré à nouveau par l’intermédiaire d’un autre ami artiste, Sorbelli, Alberto Sorbelli. Vous verrez que l’Italie est très présente dans tout ce parcours. Ça, c’était en 2005 et j’ai rencontré Pierre à plusieurs reprises, notamment dans des dîners, on riait, on discutait. Et la curiosité, quelquefois, quelque chose qui fait vilainement défaut, si bien que je ne savais pas vraiment ce que faisait Pierre dans sa vie. Et puis, quelques années plus tard, je lisais « Guerre et Paix » de Tolstoï, et dans « Guerre et Paix », il y a un Comte Apraxine. Et un soir, je suis invité à nouveau chez Sorbelli et je demande à Alberto si Pierre sera là. Il me dit : « Oui, il y aura Pierre. » Alors, dès que j’arrive, je me jette sur Pierre Apraxine et je dis : « Pierre, il y a un Comte Apraxine, comme toi. » Bien sûr, il ne l’oublie pas, et il me répond tout de suite : « Oui, mais ce n’est pas la branche de ma famille. » Et il commence comme ça à me raconter sa vie, et à me la raconter par des espèces de correspondances, notamment en parlant des lieux où il a vécu. Et cette conversation a duré plus d’une heure et demie. C’était au milieu d’un brouhaha, comme il y a souvent dans les soirées, mais moi, j’étais complètement focalisé, parce qu’il me racontait, et par l’histoire incroyable qu’il était en train de tisser pour moi. Au bout de cette longue conversation, je lui ai dit : « Mais Pierre, est-ce que vous avez jamais pensé à écrire vos mémoires ? » Et Pierre, qui était un grand homme, alors là, on voit pas vraiment que c’est un grand homme, mais c’est très grand, il avait toujours, c’était un peu dégingandé, et puis non. Et voilà, quelquefois je suis un peu lent, c’était ça, ça devait être en 2015-2016, et il m’a fallu quand même près de trois ans pour retourner constamment cette idée dans ma tête, et me dire qu’il fallait peut-être lui proposer quand même qu’il écrive ses mémoires. Et finalement, j’en parle à Jean-Michel Ottoniel, à Alberto Sorbelli, je leur demande s’ils trouvent que ce serait une bonne idée. Les deux me disent : « C’est une excellente idée, et personne ne lui a jamais proposé ça, c’est formidable, il faut que tu le lui proposes, mais il te dira non. » Alors bon, ok, je lui envoie une lettre très courte, et trois semaines plus tard, Pierre me répond : « Banco, faisons-le, à la seule condition que je n’écrive pas. » Alors, il a fallu que je réfléchisse à quelqu’un qui pourrait le faire. Et Pierre vivait à New York, moi à Paris, c’était un peu compliqué. Et Automniel, encore lui, me dit : « Bien sûr, c’est toi qui le fait, j’avais jamais pensé à cette solution-là. » Et quand il m’a dit ça, je me suis dit, en fait, il a raison, il faut que je fasse ça. Et nous avons organisé, avec Pierre, un premier voyage. C’était en novembre 2019. Pierre était très fatigué à ce moment-là, il était hospitalisé dans une maison de repos, et je suis allé le voir. Et la première conversation a été terrible, parce que, il m’a dit, « Non, non, mais on va jamais faire ça. » Moi, j’avais traversé l’Atlantique, j’étais juste là pour lui. Et il me dit, « Non, non, on arrête ça, ça n’a pas de sens, » de manière très, très virulente, quasiment virulente, alors que c’est un homme très doux, et que je l’avais toujours connu souriant, drôle. Et là, il s’est vraiment énervé. J’appelle Sorbelli, je lui dis, « Écoute, voilà, Pierre me dit qu’il ne veut pas le faire. » J’erre dans les rues de New York comme ça, et puis finalement, je trouve une cabine, et je l’appelle, et il me dit, « Non, non, mais c’est hors de question, tu es là pour ça, tu l’appelles, tu appelles son assistant, et demain, tu y retournes, tu y seras à 15h, et vous commencerez à travailler. » C’est ce que j’ai fait, et le lendemain, tout avait changé. Il y avait une éclaircie incroyable, et Pierre a commencé à me parler, à se livrer. Ça, c’était donc le premier voyage, et puis le deuxième voyage, c’était en janvier 2020. Et puis, vous savez ce qui est arrivé ensuite, il y a eu le Covid, et donc j’ai dû interrompre mes voyages, et nous avons décidé de faire des conversations téléphoniques une, deux, trois fois par semaine, jusqu’à ce que les frontières rouvrent, et que je puisse moi aussi, en fonction de mon travail, me déplacer. Et donc, je suis parti le revoir en novembre 2022, et une dernière fois cette année, en février, et une semaine plus tard, il est décédé.

, que Pierre Apraxine est l’homme d’une pensée. Sylvie Aubenas, directrice du département photographique de la Bibliothèque nationale de France, explique qu’il a le développement d’une pensée si riche qu’on a parfois du mal à le suivre. Je la cite dans un article qu’elle a écrit sur Pierre, où elle dit : « La pensée de ce lecteur de Proust se déroule en longue volute, s’étire comme un nuage aux contours impalpables. On ne comprend pas d’emblée où il veut en venir, ce qu’il voudrait. On se verrait presque du souci pour lui. Et brusquement, le nuage se change en pluie et en éclair. » Pour moi, comme je l’ai dit dès la première conversation liée aux mémoires, j’ai eu l’impression qu’il pensait par correspondance, ce qu’il a appelé une fois qu’il a commencé à lire ce que j’écrivais pour lui, des « tiroirs ». Et une autre chose s’est faite jour tout au long de ce projet, dès le début du projet, c’était pour moi la nécessité d’entendre et d’identifier sa voix, et les sources de sa voix. Elles étaient multiples. Évidemment, il y avait ce qu’il me racontait de première main. Il y avait aussi ces textes, notamment celui d’un très gros livre qu’il a écrit pour la collection qu’il a rassemblée pour Gilman, dont je parlais tout à l’heure, des entretiens avec ses amis, notamment Serge. La revue de presse très importante qu’il avait amassée, Pierre était un homme extrêmement organisé, il avait une revue de presse le concernant qui était absolument prodigieuse. Des documents personnels, notamment l’autobiographie de sa mère qu’elle avait écrite jusqu’au moment de la guerre. Et vous verrez pourquoi, l’appartement où il vivait sur la 12e rue à New York, qui n’était pas un temple de décoration, mais un lieu qui était une sorte de portrait de lui-même, où l’on avait, je ne sais pas, un fauteuil de Joe Colombo, on avait des poteries péruviennes, on avait une tapisserie d’Azerbaïdjan, on avait douze Becquists, enfin on avait des photos, bien sûr, des peintures, une très belle sculpture de Juan Cristobal, différentes choses. Et puis, il y a eu aussi son regard, et ça, c’est quelque chose que j’ai perçu un tout petit peu plus tard, quand on a commencé à rassembler ou à regarder les photos qu’on pourrait inclure dans le livre, dans les mémoires. Je me suis aperçu qu’il avait un regard très lent, en fait, quand il regarde une image, il prend beaucoup de temps, une espèce de patience qui se met comme ça en route, et finalement, au bout d’un moment, il nous pointait du doigt un détail qu’on n’avait absolument pas vu. Alors, je n’ai pas à l’esprit une image comme ça, un paysage, et tout à coup, il me dit : « Ah, vous avez vu ce champignon là ? » Le champignon, même en regardant très attentivement, je ne l’ai toujours pas vu, mais n’empêche qu’il avait ce regard à la fois synthétique, analytique, et en même temps, le souci du détail, une espèce de regard exhaustif. Et puis, il y avait aussi des conférences, et ses conférences, vous verrez, jouent un rôle très important dans sa vie, parce que c’est pour deux d’entre elles, en tous les cas, des monuments auxquels il est revenu souvent dans nos conversations. Pierre est né le 10 décembre 1934 en Estonie, avec sa famille. Ils sont partis en exil en 1939 en Belgique, et il est resté là jusqu’à la fin des années 60. À partir de 1966, il a été le conseiller du banquier Léon Lambert pour la décoration des bureaux de la banque. Quand je parle de décoration, c’était la décoration d’œuvres d’art. Ils ont été les premiers en Europe à commander des œuvres à Sol LeWitt et à Tony Smith. En 1969, il obtient une bourse de la Fulbright Fellowship, qui vous le savez, est très prestigieuse, et il est parti aux États-Unis, et il est devenu conservateur pour un département du Bowmont qui a disparu, et qui s’appelait le Hartley E. Lanning Service, qui servait à prêter ou à louer des expositions et des œuvres à des entreprises qui le souhaitaient. En 1976, il rencontre Howard Gilman, qui était un magnat du papier, le plus grand industriel papetier aux États-Unis, et Gilman lui aussi veut meubler ses bureaux d’œuvres d’art. Pierre va lui proposer trois collections, rassembler trois collections. La première, celle qu’il donne, l’art qu’il connaît, une collection d’art minimaliste et conceptuel. La deuxième, une collection de photographie. Et la troisième, une collection de dessin d’architecture utopiste. La première sera dispersée en 1987 chez Christie’s. La troisième, celle de dessin d’architecture, sera offerte au MOMA. Quant à la deuxième, celle de photographie, et bien, elle a bouleversé la vie de Pierre, et sans doute aussi la destinée de la photographie ancienne.

Voici la première image qui a donné envie à Pierre de photographier, de collectionner de la photographie ancienne. C’est une photographie de Baldus qui s’appelle « Un après-midi à la Faloise », et qu’il a achetée en 1978. Je ne ferai que citer ce passage, mais je vais vous citer deux parties du texte issues des mémoires, telles que Pierre les a formulées. Une photographie de Baldus, intitulée « Groupe dans le parc du château de la Faloise », évoque « La Cerisaie » de Tchekhov. Qui sont ces gens assis ? Cette dame de bout à droite, protégée par son ombrelle, est-ce Lioubov Andréievna Ranevskaïa, l’aristocrate dépossédée de sa propriété ? Et seul à gauche, Trofimov, l’étudiant qui rumine son suicide. Où est le marchand Pétia, qui va sauver ses méprisants amis de la ruine ? J’ai acheté cette photo à Paris en 1978. Elle a agi comme un révélateur de la collection Gilman à venir, car elle capture, comme très peu d’œuvres, l’étoffe de son époque. Sur la partie gauche de la scène, le photographe domine son modèle, qui lui obéit. Et à droite, l’appareil est libre, incontrôlé et en profondeur. À gauche, éparpillés à droite, une esthétique impressionniste avant la lettre. Il explique encore pourquoi l’importance de cette photo en la voyant. « J’ai eu la certitude que mon regard ne me trompait pas. Les amateurs de photographies de cette époque préféraient les accumulations victoriennes. J’avais, quant à moi, trop de goûts pour le minimalisme conceptuel américain pour leur porter attention. La Faloise est dénuée du détail qui fait les photographies victoriennes, le piment de l’époque. On ne sait pas vraiment qui est là, ni pourquoi. Ce type de mannequinat ne m’a d’ailleurs jamais intéressé. Ici, c’est tout un monde que l’on porte en soi, tout ce que l’on y met, l’impressionnisme, la cerisaie, etc. Évidemment, Baldus n’a pas pu y penser, mais ce qui fait de cette photographie un chef-d’œuvre réside précisément dans ce que le photographe n’y a pas mis, dans les correspondances que nous lui trouvons. J’étais certain qu’il fallait l’acheter. Elle était très chère, et je n’avais pas encore la bourse de Harvard. Je suis rentré à New York et lui ai dit qu’il nous fallait cette photographie. Non seulement nous devions l’acheter, mais c’était cela, ces photographies anciennes-là, qu’il fallait collectionner. La collection Gilman était là, le rêve de tout collectionneur, et de faire de sa collection un objet unique. Avec cette photo, j’en entrevoyais la possibilité. »

La collection donc démarre en 1978, et petit à petit, elle va prendre corps et se développer assez rapidement. Si bien que elle va attirer l’attention du Metropolitan Museum de New York, et notamment de la directrice du département de photographie, qui était Maria Morris Hambourg, et qui s’est fait très vite une mission de pouvoir un jour acquérir cette collection, qui était encore en devenir. Je l’ai dit, il y a deux conférences importantes dans la vie de Pierre, en tous les cas, deux conférences qu’il a citées, qu’il m’a citées abondamment, sur lesquelles il est revenu très longuement. Une conférence autour de la Castiglione, et une conférence autour du Waiting Dream. Le Waiting Dream, c’est une exposition qu’ils ont organisée en 1993 au Metropolitan Museum. C’était un événement absolument hallucinant, parce qu’il n’y avait jamais eu quelque chose de cet ordre-là qui avait été fait dans les murs du Metropolitan. Dans sa conférence pour le Waiting Dream, qui précède chronologiquement celle sur la Castiglione, Pierre évoque la Castiglione, mais à l’époque, il n’a pas encore travaillé sur le sujet. Cependant, le connaissant, il a dû déjà avaler le livre de Montesquieu consacré à la comtesse, et dont Gérard Lévy lui avait offert un exemplaire. Il avait également déjà acheté toute une série de photos tirées de la série des Roses, où la comtesse est vieillissante, où elle n’est plus que l’ombre d’elle-même. Il avait d’abord rejeté la comtesse, malgré l’insistance de François Brunsweig et Hugues Autexier, qui étaient des marchands avec lesquels il travaillait beaucoup, et qu’on appelait d’un mot valise « Les TexBraun ». François Brunsweig et Hugues Autexier avaient essayé longuement de convaincre Pierre, et lui se refusait toujours à s’intéresser à la comtesse, jusqu’à ce qu’il tombe sur cette série des Roses. Voici, en tous les cas, ce que dit Pierre dans la conférence qu’il donna à New York sur la comtesse. « Très tôt, François Brunsweig et Hugues Autexier se sont intéressés à la Castiglione, et vers 1980, ils m’ont montré une image qui, je pense, était celle de la Reine des Reines. La photographie baroque du 19e siècle ne m’intéressait pas à cette époque. Je recherchais des images du 19e siècle avec une esthétique minimaliste très contemporaine, et ne parvenait pas à m’attacher à l’artificialité des créations de la Castiglione. En 1985, j’ai acheté, avec le Musée d’Orsay, trois livrets de photographie des dernières années de la comtesse, 1893-1895. Ce qui était baroque est devenu grotesque, un grotesque où il était difficile de séparer la nostalgie de la caricature, aux prises avec un lourd contenu psychologique. Cela a commencé à m’intéresser. En 1992, préparant l’exposition de la collection Gilman, du Waiting Dream pour le Metropolitan Museum, j’ai acheté le regard+ ».

C’est avec cette photo que j’ai appris que les négatifs étaient conservés à Colmar, en France, et bien sûr j’ai fouillé la collection de ces photographies conservées au Metropolitan, provenant de la collection Robert de Montesquieu, et j’ai lu son hommage à la divine comtesse. Fin ’94, je pensais déjà à une exposition. L’exposition aura lieu donc en 2000, comme je le disais tout à l’heure. Il a donc voulu, pour le « Weeking Dream », inclure une photo de la Castiglione, mais une image différente de celle des vieilles années de la comtesse. Une photo qui s’intitule « Le Regard » et qui fait partie des premières photos qu’elle fait faire à Pierre, son photographe, sous sa direction. Deux images importantes, à deux moments de sa vie, disent tout de la démarche de la comtesse.

Béatrice résume sa démarche, nous dit Pierre. La photographie a été réalisée en 1856-1857, mais le titre vient d’une pièce jouée à Paris en 1861. « Béatrix sacrifie son amour pour un prince contraint de se marier avec une princesse pour la raison d’État ». La comtesse écrivit à propos de Béatrix : « Quand le chagrin est si beau à voir, qui pourrait souhaiter le bonheur ? » Et puis, une autre très connue, « schizodifolia », en étonne notre exemple, nous dit-il. Le titre est tiré de l’opéra de Verdi « Un ballo in maschera », un bal masqué, lorsque le roi s’adresse à la sorcière qui a prédit sa mort. « Est-ce une blague ou une folie ? », pour la question, le titre mêle les deux. Il faut savoir que lors de la création de l’opéra à Naples, dans la scène du bal masqué, les figures en féminin étaient jouées par des dames du monde, bientôt remplacées par des courtisanes et des prostituées. Lorsque la comtesse est à nouveau invitée à la cour de Napoléon III en 1863, après cinq années d’exclusion, au fameux bal où elle porte le costume de la reine Destreriès, elle répond que « si d’autres invitations devaient suivre, je ne veux pas comparaître comme un figurant du bal et une masquero ». Ce titre deviendra une référence constante pour la comtesse. Elle était très sensible à toute affaire sociale. En effet, sa position était précaire, séparée de son mari. Elle se maintient dans la société grâce au soutien de son ambassade, évitant ainsi d’être confondue avec une courtisane, même si elle semble vivre bien au-dessus de ses moyens. Il est donc assez étonnant qu’elle se soit risquée à incarner une courtisane dans ses photographies. Cette image ne doit pas être prise au pied de la lettre, conclut Pierre. C’est une aristocrate jouant à la petite vertu.

Quelques années auparavant, Pierre a présenté une autre conférence au moment de la présentation de l’exposition « Waking Dream ». Cette conférence s’est tenue le 13 juin 1993, et il a fixé un cadre temporel à cette conférence, un cadre temporel qui utilise des références littéraires et françaises. D’une part, il utilise « Madame Bovary », qui est publié en 1857, et le premier volume de « La Recherche du temps perdu », qui paraît en 1913. Voici comment il justifie son choix : « Le grand projet de ses romans était, selon les mots de Milan Kundera, l’exploration des dimensions intérieures des lettres. Dans cette période d’introspection et de culture de soi, on peut imaginer faire dans le travail des photographes une riche moisson d’indices autobiographiques. Ces indices, nous l’espérons, nous aideront à atteindre la dimension intérieure. Ce faisant, nous pourrons peut-être mieux saisir pourquoi certaines images ont une telle emprise sur notre imaginaire ». Dans cette conférence, Pierre explore six destins de photographes, femmes et hommes. Il nous annonce assez malicieusement qu’il a renversé la proportion entre hommes et femmes, puisqu’il traite de 4 photographes femmes et de deux photographes hommes. 5 de ces photographes sont représentés dans la collection Gilman, une ne l’est pas. Il s’agit de Sophia Tolstoï, la femme de l’écrivain. Il inclut aussi à son exposé une autre photographe russe, une représentante de la famille impériale, une des sœurs du tsar, la Grande Duchesse Xénia. C’est une raison assez choquante. Nous sommes donc en ’93, l’exposition de « Waking Dream » vient d’ouvrir, c’est un succès absolument immense, un événement que le musée salue comme tel, puisque les photographies sont présentées dans le parcours des chefs du musée, ce qui n’avait été fait, je crois, qu’une fois auparavant. C’est donc un moment absolument exceptionnel, et tous les gens qui ont vu l’exposition, voire qui ont assisté à son vernissage, se rappellent une présentation et une fête inoubliables. Vous imaginez que pour les co-commissaires, qui étaient Pierre Apraxine et Maria Maurice Hamburg, la directrice du département de photos, se durent être des moments absolument magiques. Au-delà de l’exposition, Pierre devait travailler à la tournée de l’exposition, puisqu’elle irait ensuite à Édimbourg et à Washington. Or, à ce moment-là, il fait face à des problèmes de santé grave qui le préoccupent et l’épuisent, et par ailleurs, il vient de perdre sa mère et l’un de ses amis très proches. Et donc, il est confronté à la mort de manière très vive. Et puis, quelques semaines plus tard, il devra faire son premier grand voyage de retour en Russie. Sans doute son esprit est-il, à ce moment-là, aussi accaparé par la perspective de ce voyage. Tout cela pour dire que la conférence qu’il fait représente un enjeu personnel pour lui. Rien n’est jamais académique chez Pierre Apraxine. Tout doit relever, dans une certaine mesure, de l’expérience humaine. Il n’y a pas d’échelle de valeur inabstracto de l’art. Et si sa façon de regarder la photographie et de l’éclairer, et celle de l’expert, le choix de ce qu’il regarde, relève de choses intimes. Dans cette conférence, il parle tout d’abord de la Castiglione, puis de Sophia Tolstoï, puis de la Grande Duchesse Xénia, puis de la comtesse Greffeuille. Cet ordre m’intéresse. Il a la forme d’un pantoum baudelairien où les rimes ne sont pas croisées, comme dans la forme originale du pantoum, mais où deux rimes en embrassent deux autres. Je vous cite, pour vous éclairer, une strophe de « L’Harmonie du soir », qui est un pantoum de Baudelaire : « Voici venir les temps où vibrant sur sa tige, chaque fleur s’évapore ainsi qu’un encensoir ; les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir, valse mélancolique et langoureux vertige ». Donc, tige, vertige, et au milieu, encensoir, soir. Il encadre les deux nobles russes par deux nobles françaises qui ne sont pas elles-mêmes photographes, mais font œuvre de photographie. Quelles raisons pour évoquer la Castiglione et la comtesse Greffeuille ? Quand quelques années plus tard, Erwin, qui était un ami de Pierre, a vu l’exposition sur la question, il a dit : « Mais la Castiglione, c’est Pierre ! Je ne dirais pas autre chose que cela ». Et je vous renvoie au livre que nous publions l’an prochain. Mais pourquoi la comtesse Greffeuille ? Voici ce qu’on dit Pierre.

Madame Greffeuille était considérée comme la beauté suprême de son époque et la reine de la haute société parisienne. Marcel Proust, qui a fait sa connaissance en 1892, a été envoûté par sa beauté, l’élégance de sa personnalité et son aura de glamour absolu. Elle est devenue le modèle de la duchesse de Guermantes dans « La Recherche du temps perdu », et Proust l’a sollicitée pour sa photographie, ce qu’elle refusa catégoriquement, considérant les photographies comme privées et intimes, à ne pas donner aux étrangers. On peut se demander pourquoi Madame Greffeuille a-t-elle commandé un portrait aussi déroutant où elle et son double semblent engagés dans un jeu de deux rêveurs. Le portrait a été réalisé par Otto, le photographe à la mode des belles femmes et des enfants, qui avait un atelier place de la Madeleine à Paris. Son rôle ici, cependant, est similaire à celui que le fidèle Monsieur Pierson joua aux côtés de la comtesse de Castiglione. Le bon Monsieur Otto n’aurait jamais osé concocter par lui-même une telle composition. Comme la comtesse avant elle, Madame Greffeuille est l’auteure de son portrait. Oublions donc Otto, sinon simplement qu’il a prêté son savoir-faire dans la combinaison des deux négatifs. Quelle est la jeunesse d’une telle image ? Le thème du double, entre la littérature du 19e siècle, d’Edgar Allan Poe avec « William Wilson », à Robert Louis Stevenson avec « Docteur Jekyll et Mister Hyde », et Oscar Wilde avec « Le Portrait de Dorian Gray ». La confrontation avec un sosie mène toujours au drame. En photographie, cela prend généralement une tournure fantaisiste, mais le portrait de Madame Greffeuille est très sérieux. D’abord, les yeux de Madame Greffeuille, à qui Proust attribuait le véritable mystère de sa beauté, sont ici inopinément fermés ou détournés. Ensuite, nous avons la robe qu’elle porte, la blanche, totalement impraticable, étant en fait un drapé, ce qu’Otto a transformé en un objet merveilleux de l’Art Nouveau, mais aussi en une sorte de fantôme. On voit aussi l’opposition entre la jupe et le corsage blanc et la robe de bal en taffetas plus foncé. Et qu’en est-il de la pose elle-même, où la silhouette sombre semble sortir de la plus claire ? Nous savons, par une biographie récente, que Madame Greffeuille s’intéressait au spiritisme. Elle partageait cet intérêt avec des personnalités les plus éminentes de son temps, comme le mathématicien Poincaré et l’astronome Flammarion. On suppose ainsi que la plus sombre Madame Greffeuille est en effet une émanation de la plus claire. Se pourrait-il que ce portrait tente de donner forme à une partie de la personne dont l’expression demeure généralement cachée derrière la façade d’une vie sociale très disciplinée ? Nous savons, d’après certaines de ses notes, qu’elle avait travaillé très dur pour créer le personnage que tout le monde admirait comme Salambo. Elle ne se montrait jamais à la foule que du haut de son escalier ou entourée de rois s’il y en avait dans sa vie privée. Cependant, Madame Greffeuille n’avait pas la même chance. Elle avait la réputation d’être la femme la plus trompée de Paris. Le double plus sombre de Madame Greffeuille peut naïvement faire allusion à cette partie plus méconnue d’elle-même qu’elle gardait jalousement sous clé, comme elle l’a fait avec ce portrait qui ne quittait jamais ses appartements privés. Et bien sûr, il y a un élément narcissique dans ce portrait. Ce n’est pas inattendu de la part d’une femme aussi admirée, qui a dû passer de nombreuses heures devant son miroir qu’elle nommait « Celui qui ne sait pas aimer ». Pour toujours, je crois qu’elle a conçu cette photographie, qu’elle a présentée avec des traits idéalisés sur lesquels le temps n’a pas de prise, comme un miroir qui aurait bien la dimension d’un miroir. Un miroir qui reflète ce qu’elle ressentait être son véritable désir et qui ne la trahirait pas, mais resterait pour toujours un ami fidèle.

Sauf qu’à l’inverse de la comtesse de Castiglione, la comtesse Greffeuille n’a pas traumatisé un photographe durant 40 ans. La Castiglione, elle, a toujours utilisé les services du même photographe pour prendre des photographies d’elle, le fidèle Pierson, comme disait Pierre. Et donc, l’entreprise de la comtesse Greffeuille avec le photographe Otto demeure exceptionnelle. Sa présence dans la présentation de Pierre offre non seulement un pendant à celle de la Castiglione, mais aussi au sujet de l’exposition qui suivra celle de la comtesse, l’exposition que Pierre consacrera à la photographie spirituelle.

Les deux autres photographes femmes que Pierre Apraxine évoque sont deux nobles russes et deux témoins d’un monde auquel Pierre dit avoir appartenu sans jamais l’avoir connu, la Russie d’avant la Révolution d’Octobre. Tout d’abord, une femme d’exception, la comtesse Sophia Tolstoï, femme de l’écrivain et photographe Sofia Andrieu. Elle épousa Léon Tolstoï en 1862, alors qu’elle avait à peine 18 ans, et lui, déjà 34 ans, était un écrivain célèbre. Pendant près de 50 ans, Sophia Andriefna sera la secrétaire de son mari, copiant ses manuscrits, corrigeant les épreuves, traitant avec l’éditeur, et elle mit au monde 12 enfants tout en gérant leur propriété de campagne. En 1887, elle achète un lourd appareil photo Kodak sur trépied, et pour ces photos, elle utilisera un négatif sur verre qu’elle devra développer. Elle ne commença vraiment à se consacrer à la photographie qu’à partir de 1895, pour se distraire de la mort de son plus jeune fils, et elle arrêta de photographier à la mort de son mari en 1910. Elle-même mourut en 1919, pendant la Révolution. Elle laissa plus de 800 négatifs, qui sont conservés au Musée Tolstoï de Moscou, et en 1911, elle publia une sélection de 120 d’entre eux dans un album de phototypies vendu à des fins caritatives.

Pierre nous fait remarquer à quel point Sophia Andriefna était vraiment une bonne photographe. Tolstoï détestait poser pour les peintres et les sculpteurs, alors Sophia réalisait des études pour eux. Ici, sur cette très belle photo de 1909, elle a surpris Tolstoï dans un moment d’intense et fort mental. L’objectif est braqué sur sa tête chauve, l’espace autour du personnage s’effondre en un seul plan aplati, et la table et le papier deviennent un piédestal soutenant le buste de l’écrivain. La photographe nous montre Tolstoï tel qu’elle voulait que nous le voyions, un géant entré dans l’histoire, oublié de son environnement, vivant dans l’énergie comprimée de son esprit. La grande période de production photographique de Sophia Andriefna coïncide avec la période la plus difficile de son mariage, et son sentiment de tragédie imminente traverse sa chronique. A-t-elle utilisé la photographie comme un divertissement ou répondait-elle enfin aux besoins de donner à la vie sa propre expression ? Savait-elle que ses plus belles images contenaient une indiscrétion brutale ? Quelle que soit la réponse, son travail, si intimement lié à la vie de son mari, n’en reste pas moins digne d’intérêt. Dans l’un de ses journaux, elle dit que son mari est contre « l’immense émancipation des femmes, contre la soi-disant égalité des droits », et que peu importe ce que la femme faisait, qu’il s’agisse d’enseignements de médecine ou d’art, elle n’avait qu’un seul but réel dans la vie, et c’était l’amour sexuel. De sorte que quoi qu’elle puisse s’efforcer d’accomplir, ces efforts s’effondreraient simplement ensemble. Le travail de Sophia Andriefna est son meilleur démenti.

Si la Castiglione a produit plus de 800 photographies en 40 ans, Sophia en a fait le même nombre en 15 ans, et la Grande Duchesse Xénia plus de 1 120 en moins d’un an. La photographie était une obsession de la famille impériale russe. Ses membres emportaient partout leur appareil photo Kodak et faisaient énormément de photos. L’album issu de la collection Gilman a été réalisé par la Grande Duchesse Xénia, comme je le disais tout à l’heure. Et elle est l’une des sœurs du tsar. Cet album date de 1904-1905, année de la guerre russo-japonaise et des premiers craquements réels dans la société russe. Cet album ne s’en fait pas du tout le reflet, tout juste montre-t-il parfois le tsar bénissant les troupes partant au front. Mais on voit que bien souvent, ce sont plutôt des scènes d’amusement et des scènes intimes qui sont décrites. Écoutons Pierre.

C’est dans ce contexte tumultueux qu’il faut apprécier l’album de la Grande Duchesse, journal intime ou film amateur, cela n’affecte pas le ton. Il montre un amour du plaisir simple qui contraste avec la grandeur des palais et des parcs. Mais les abords privilégiés sont en fait des caches dorés des forteresses, comme Gatchina, où la famille passe tant de temps, parce que ce n’est que là qu’elle se sent en sécurité. En dehors, les grands ducs et leurs familles étaient des cibles. Ils en étaient conscients et ne l’oubliaient jamais. Ce qui explique peut-être le plaisir qu’ils prenaient à s’observer vivre et l’accumulation maniaque d’images de petits plaisirs et de bonheur domestique.

Pierre et Gilman étaient homosexuels. Ils n’en faisaient pas de leur homosexualité une bannière, mais ne la cachaient pas non plus. Et comme tout ce qui est au fondement de la façon de collectionner de Pierre, elle pouvait prendre une part dans ses choix artistiques.

Issu d’une famille aisée du Massachusetts, Frederick Holland Day fonda la maison d’édition Copeland & Day et publia l’édition américaine de « Salomé » de Wilde, dont il devint un ami. C’est l’intérêt de Holland Day pour la littérature qui le conduit à la photographie. En tant que photographe, il se fit connaître avec la série « Nubian » de 1896 et 1897, où il photographiait son chauffeur noir, Alfred Daniel, en chef africain. Pierre nous dit encore plus, comment érotique l’image du nu apparaît ici, simplement comme une référence au classicisme. Holland Day fut l’un des premiers photographes à concevoir le nu non pas à travers le prisme du pittoresque, mais à travers celui de l’idéal classique. L’effet global recherché par le photographe est celui d’une sérénité hellénistique, païenne. Sa démarche est aussi certainement loin des études pseudo-anthropologiques des humanistes d’autres photographes, comme Charnay, dont les images se voulaient classées dans l’histoire naturelle. Holland Day appartient à l’histoire de l’art depuis l’époque du mouvement romantique. L’Europe et le monde occidental, en général, avaient ressenti le besoin d’échapper aux normes d’une société bourgeoise de plus en plus étouffante et de rechercher un exotisme. Il existe en cela une longue tradition littéraire et visuelle. Dans une lettre à George Sanders, il écrivait : « Contrairement à vous, je n’éprouve jamais un sentiment de vie qui ne fait que commencer. Mon moi actuel est une conséquence de tous mes mois disparus. J’étais batelier sur le Nil, proxénète à Rome au temps des guerres puniques, puis rhéteur grec à Suburra, où j’ai été dévoré par les punaises de lit. Je suis mort pendant les croisades pour avoir mangé trop de raisin sur la plage de Syrie. J’étais pirate et moine, certaines banques est-cochées, et peut-être empereur d’Orient, qui sait ? »

La passion pour les voyages et singulièrement pour l’Égypte a traversé toute la vie et la recherche de Pierre Apraxine. Son regard s’est longuement porté sur l’œuvre d’un photographe américain mort à 24 ans, Jay B. Green, dont la vision des paysages égyptiens recoupait le goût de Pierre pour l’art minimaliste et conceptuel, sans que pour autant les deux puissent être associés comme on a pu être tenté de le faire. Et c’est cette sobriété, cette quasi-disparition du sujet, entre abstraction et évanescente, qui nous ravit. Mais c’est notre œil du 21e siècle qui réagit aussi probablement, pas celui d’une personne du Second Empire qui aurait trouvé cette photographie si vide qu’elle en est sans sujet, alors que l’inaccessibilité de ce même sujet nous ravit, parce que nous avons lu « Le Désert des Tartares » de Buzzati et aimé l’économie extrême de Marguerite Duras. Les paysages du Nil vus dans la photographie ancienne ont donné lieu d’ailleurs à une très belle exposition imaginée par Malcolm Daniel, puis organisée par Pierre et Jeff Rosenheim, inaugurée au Metropolitan Museum le 10 septembre 2001, et à laquelle je crois que Serge a assisté. On se rappelle de quoi le 10 septembre et la veille.

Son vrai transition dans sa conférence, mais nous introduisons à l’une des images qu’il m’a le plus commenté dans nos conversations. Pierre évoque l’autoportrait de Stanislas Ignac. Je vous cite une étendue analyse qui nous apprend tant de choses de sa vision de l’art et de la vie. Créée vers 1912, alors que Witkiewicz avait 27 ou 28 ans, ce portrait ne ressemble à rien de ce qui a été vu jusqu’à présent en photographie. En effet, la recherche de la vérité psychologique culmine dans un défi douloureux. Recadré pour mettre en valeur et se concentrer sur les yeux, le visage de Witkiewicz se soumet à une interrogation impitoyable. Son regard est tout intérieur, il perce les carapaces protectrices érigées par le moi pour atteindre son fondement même. Il affronte de front le mystère de la conscience et son corollaire, l’angoisse existentielle. Il ne suffit pas, écrit Witkiewicz, « d’exister simplement, sans réfléchir passivement, négativement. Il faut manifester plus clairement l’existence sur fond de mort possible et de néant environnants ». Tel était le programme de la vie de Witkiewicz, dans l’art, poursuivi avec une vigueur inlassable à travers ses nombreuses activités : peinture, photographie, théâtre et philosophie. Son travail est aux prises avec le thème sous-jacent de toute la pensée du XXe siècle : l’absurdité essentielle de l’existence. Ce premier portrait ferme la porte aux précédentes tentatives d’auto-définition. C’est une image de la condition des hommes contemporains.

La photographie est au 19e siècle l’instrument d’une émancipation, sans doute pas dans des termes historiques ni sociologiques, mais tout de même la marque d’une liberté. Pierre avait observé cette liberté chez sa mère, qui avait été obligée de travailler après la guerre. Elle croyait toujours que son mari était en vie, mais il n’était pas revenu de la guerre. En réalité, il était mort, et elle fut privée de ressources par sa famille, qui désapprouvait sa manière d’éduquer ses fils. Cette femme qui se réveille dans sa jeunesse, pianiste concertiste, devint comptable.

Pierre était aussi le petit-fils de la femme d’un gouverneur de l’Empire russe, assassiné au début de la Révolution. Ce grand-père s’était ingénié à rebâtir le domaine estonien où Pierre passa les cinq premières années de sa vie, et où il n’eut de cesse de revenir, notamment avec vous, Serge. Pierre avait ce rêve des grands espaces qu’il avait quitté enfant. La vie s’est chargée de lui rappeler que certains rêves sont des fantasmes stériles, et qu’il y a bien plus dans ce que l’on a accompli dans l’intervalle. Il y a une œuvre indélébile, portée à bout de bras pendant près de 30 ans, durant la vie de Howard Gilman et au-delà, pour que la collection Gilman, créée par Pierre, conserve son intégrité en entrant au Metropolitan Museum de New York. Sa vision de la vie était en accord avec sa façon de collectionner : curieuse, généreuse, honnête, bienveillante. Pierre était, comme nous tous, pétri de défauts, mais plus que beaucoup d’entre nous, un homme essentiellement bon. Étrangement, je crois que cela a participé à sa capacité à assembler la plus belle collection de photographie ancienne au monde. Cette œuvre incomparable fait de lui un merveilleux artiste. Laissons-le conclure.

Revenons maintenant sur ce que nous avons appris dans notre tour de ces images. Ce n’est pas très édifiant. Nous avons entendu le soliloque déchirant de la comtesse de Castiglione, perdue dans une galerie de glace. La vie de Sophie Tolstoï sans son mari est comme une boîte vide, et la Grande Duchesse Xénia est le partenaire silencieux de l’histoire elle-même qui attend son heure. La comtesse Greffeuille, Frédéric Hollandais, dévoile dans une délivrante confession le caractère ambigu de leur désir, et le désespoir de Witkiewicz à la densité noire d’une étoile effondrée. Le bilan n’est pas réjouissant, mais aurait-il pu en être autrement ? N’est-il pas inhérent à la nature de la vie d’afficher son caractère incomplet, et dans la nature de l’art de chercher du sens et de l’unité à cheval sur la vie et là ? Comment la photographie pourrait-elle ne pas révéler le dilemme essentiel de ce créateur ?

Je déteste vous laisser avec cette question, ajoute-t-il. L’une des photographies les plus populaires de l’exposition s’intitule « Qui sont-ils ? ». Elle montre un groupe revenant d’une chasse au renard dans la campagne romaine, photographiée par le comte Primoli en 1899. Où réside la très poétique et amère densité de cette image ? N’est-ce pas dans la tension entre les silhouettes verticales des personnages en mouvement et la ligne d’horizon, dans laquelle, attirés comme par un aimant, ils sont voués à disparaître ? Les personnages poursuivent leur course, chacun à son rythme. En effet, nous ne saurons jamais qui ils étaient vraiment, mais nous savons qu’ils disparaîtront, nous laissant méditer sur le gracieux souvenir de leur passage.

On en sait un peu plus sur la vie des photographes que nous avons examinés. Comme ces chasseurs, ils ont maintenant dépassé l’horizon, nous laissant poursuivre notre propre voyage, enrichi par l’expérience et peut-être, qui sait, à notre insu à cet instant précis, un photographe recueille dans une image la poésie singulière de notre cheminement.

Et Pierre dit encore, comme je le fais aussi, merci.

Voilà, merci beaucoup. Bon, je pense s’il y a des gens qui veulent poser des questions… Je veux juste ajouter une chose tout de suite, un peu aussi de la part d’un membre de la famille de Pierre qui avait essayé de venir, mais n’a pas pu venir, de donner un détail. On dit qu’il est né en Estonie, parce qu’en fait l’endroit où il est né était sur la carte de l’Estonie en 1934, mais il est né dans quelque chose, un endroit, un espace politique géopolitique assez difficile à décrire. Vous connaissez un peu l’histoire de la Russie, de la Révolution bolchevique, des guerres qui ont suivi, qui ont été fort longues. Mais la paix, la première paix qui a été signée par le régime bolchevik, a été avec les pays baltes, pour la frontière du Nord-Ouest, et à la création des pays baltes, il y a une vallée qui s’est retrouvée de l’autre côté, et elle s’est retrouvée de l’autre côté pour une vingtaine d’années seulement, autour d’un monastère qui s’appelle le monastère de Pechory, et vivait là 15 000 russes, surtout des paysans, mais également quelques moines dans le monastère. Il se trouve qu’une des immenses propriétés appartenant à la grand-mère de Pierre était dans cette région, et le premier président de la République estonienne, qui avait une sorte de dette d’honneur parce que le grand-père de Pierre, qui a été gouvernant militaire, a été tué par un sniper pendant la Révolution de février, a gracié des prisonniers politiques baltes et estoniens. Et donc l’homme qui devient le premier Premier ministre de ce pays désormais indépendant devait la vie quand même au fait d’avoir été gracié, et il propose à la grand-mère de reprendre une partie des terres. J’en profite pour raconter, reprendre une partie des terres, parce que les Estoniens, le gouvernement estonien de ce pays qui retrouve l’indépendance pour la première fois, appliquent une collectivisation, quand même une demi-collectivisation, même si elle possédait par exemple 50 000 hectares, elle avait le droit d’en reprendre 50, 50 par personne qui viendrait vivre là. Mais de toute façon, la grand-mère a décidé d’y retourner, car c’était le seul morceau de Russie qui a survécu avec ses anciennes traditions, avec sa paysannerie, avec ses rites orthodoxes, avec ses pops, le seul morceau où 15 000 russes sont restés. Et la grand-mère de Pierre était le personnage le plus important de cette région, et elle a même organisé les visites d’ethnographes du monde entier, qui sont venus voir, car ils se rendaient compte de la fragilité de cette survivance. La suite de tout ce qui s’était passé, en particulier dans les années terrifiantes de la Terreur rouge de Staline. Donc elle organisait des séminaires en été, un festival de santé populaire. Et Pierre a donc vécu les cinq premières années, parlons russe, vieux russe, dans une anomalie de l’histoire. Voilà, je voulais juste compléter comme ça.

Je peux raconter ça aussi, je vais raconter ça aussi. 10 septembre 2001, le Metropolitan Museum avait décidé d’organiser, pour la première fois, une exposition sur la découverte du tombeau de Toutankhamon. Il s’agissait d’une grande exposition du département d’antiquités égyptiennes. À cette occasion, le département de photographie, avec Pierre, avait travaillé sur une petite exposition de photographie, en comparaison avec le nombre de salles impliquées. Et avec Inès, nous avons été invités. J’avais trouvé un billet avec Icelandair. Nous sommes arrivés à New York. Inès s’était foulé la cheville, et Pierre avait organisé qu’elle puisse être promenée. Nous avions un petit fauteuil très confortable. Et nous sommes arrivés. La fête était grandiose, grandiose à l’américaine, à la new-yorkaise, c’est-à-dire qu’il y avait le temple d’Endou. Vous savez, le temple que l’Égypte a offert aux États-Unis, le temple complet qui a été démonté bloc par bloc et remonté dans une aile du musée métropolitain. Il y avait des petits fours partout, de l’alcool à flot, des tambours, d’énormes candélabres tenant des feux, pas des… c’est pas des bougies, c’était des véritables… ça s’appelle photophore, je sais pas. Mais de grande taille. Et surtout, vous aviez ces énormes baies vitrées sur Central Park, comme vous avez ici sur l’Adriatique, avec à l’extérieur des nuages noirs et un ciel déchiré d’éclairs, comme si c’était la colère absolue de Toutankhamon. Le tout, le monde était très, très effrayé par cette tempête soudaine. Et donc le lendemain, quand nous sommes réveillés, il y avait les télévisions qui étaient interrompues. On voyait de la fumée, on voyait des choses. Je me rappelle être monté sur le toit de l’hôtel. Nous avons réussi à joindre Pierre, qui nous a invités à le rejoindre tout de suite en disant : « Attention, les téléphones marchent de plus en plus mal ». Nous avons pris un taxi. Je me rappelle, on a vu même, il y avait tous ces gens qui couraient, couverts de plâtre, qui venaient dans l’autre sens. Pierre habitant à la douzième rue Ouest, nous nous rapprochons en fait du sud de Manhattan. Et nous avons été accueillis chez lui. Nous avons donc vécu quelques jours, Inès étant une jeune maman avec des enfants en bas âge. Heureusement, on a réussi à joindre une seule fois les grands-parents pour qu’ils s’occupent de nos filles à Paris, en France. Et avec Pierre, on avait décidé, on avait supprimé les journaux, coupé la radio. Il n’avait pas la télévision, pour qu’il n’ait pas à s’inquiéter et puisse lire des livres de poésie et tout ça. Et nous, nous sortions tous les deux dans la rue, essayant de glaner des informations. Et je me rappellerai toujours un soir, nous sommes sur Houston Street, qui était la rue la plus proche des deux tours jumelles. Le quartier avait été interdit, barricadé. Il y avait la foule dans un bar, et la télévision du bar montrait CNN. Il y avait un reportage, et tout d’un coup, est apparu le portrait de Ben Laden. Et Pierre disait : « Mais je sais pas comment ils ont fait ça, mais c’est incroyable par rapport à toutes ces images médiocres, confuses, ce vacarme, ce bruit, s’il avait tout d’un coup ce portrait, qu’il est beau ». Donc, je fais attention à ce que je dis, mais l’analyse, la force des images, la façon de Pierre, venant d’une famille, d’un pays qui a connu énormément de violence et dans les moments de choses, et sa manière toujours de regarder, de chercher une élégance, une quelque chose à dire, un commentaire, même dans les moments les plus incroyables. Je viens, je reviens de New York, moi. J’avais vu Pierre la dernière fois, c’était au mois de janvier cette année. J’allais le voir assez souvent. Et là, le Joe, son secrétaire, m’avait dit que si j’étais passé à New York, il y avait deux, trois choses à prendre, de trois livres. Et puis, il y avait une petite photo que je vous ai amenée pour vous montrer, parce qu’on n’a pas arrêté d’en parler. Donc ça, c’est mon héritage. C’est un petit portrait de Léon Tolstoï jeune. Vous venez de voir Londal, en 1849. Il n’y a pas de photographie sur papier en Russie. C’est en fait une reproduction d’un daguerréotype aujourd’hui disparu, et c’était une photographie en or que j’avais découverte dans un de mes voyages, parce que j’allais souvent en Russie, et Pierre aimait beaucoup que je lui raconte les aventures russes. Et donc voilà, je lui ai cédé, et il me l’a retournée. Voilà, je vous invite à le regarder tout à l’heure.

Je ne sais pas si vous voulez savoir quelque chose, si quelqu’un veut poser une question, car là vous avez le biographe, l’auteur éditeur des mémoires. Donc, c’est une occasion rare.

Juste pour reprendre ce que vous disiez à propos du grand-père qui a été assassiné, Pierre avait de multiples versions de cette histoire parce qu’il n’était pas sûr de ce qu’on lui avait raconté ou de la vérité. Il était toujours, et c’est ça qui était très beau dans son regard, c’est qu’il savait qu’il y avait la légende et la vraie histoire, et ça c’était aussi toujours dans son regard, dans la photographie. Enfin, il me semble que lorsqu’il regardait une image, il regardait ce qu’il y avait à voir et au-delà, et notamment dans ce meurtre, on lui a raconté toute sa vie qu’il avait, que son grand-père faisait un discours ou aller faire un discours, enfin bon, voilà, et qu’il y avait un sniper qui est là-dessus. En vérité, il a été trimballé, enfin tout de suite on est allé le chercher dans son palais qu’il avait, que le grand-père avait fait évacuer pour que personne d’autre que lui ne soit tué. Et il a été tout de suite sorti dans la rue et traîné, et sa tête découpée, enfin ça a été une boucherie invraisemblable, quoi. Pour les gens qui s’intéressent un peu, je vois qui s’intéresse un peu à l’histoire de la première révolution, celle de février qui a donc eu en mars 17, le grand-père, le général Von Bounting et gouverneur de la région de Dvers. La région de Dvers, si vous avez pris le train de nuit le « Krasnai Streilla » entre Moscou et Saint-Pétersbourg, c’est à mi-chemin. Et cet endroit est stratégique, parce que, au début de la Révolution, il y a une des deux capitales russes qui est du côté révolutionnaire, l’autre qui n’est pas encore, et donc le gouverneur au milieu aurait peut-être pu faire basculer l’issue du conflit encore incertain. Il est donc dans son palais de représentants du pouvoir impérial qui a été attaqué, voilà, c’est la version, et selon la version de Pierre, c’est un sniper. Il n’était pas sûr après.

Pendant que, pendant qu’il y a les préparatifs de l’atelier de photographie à travers une boule de cristal, je vais raconter quand même aussi une des missions en Russie que m’avait confiée Pierre, parmi les plus complexes qui a eu lieu la même année, 2001. Il me créditait de beaucoup d’intrépidité et donc, il m’a dit, je sais pas qui est-ce qui pourrait résoudre ça, mais on peut essayer. Il me dit : « Voilà, voilà le sujet. Il y a ce monastère qui est pas loin de l’endroit où je suis né, ce monastère de Petchora. C’est un monastère qui est redevenu après la perestroïka occupé par les moines, et qui est un lieu maintenant très important de pèlerinage. Et il faut essayer d’y arriver. Il faut essayer de négocier avec les moines d’obtenir la clé des catacombes. Dans les catacombes, il y a un moment, un tunnel qui est à nouveau fermé par une autre clé. Il faut essayer d’obtenir celle-là, qui est encore plus difficile, et il faut aller vérifier les inscriptions sépulcrales des tombeaux d’une certaine grotte. »

Et il dit : « Je sais pas comment, je pense que là, pour atteindre le monastère qui n’est pas vraiment indiqué sur les routes et où les étrangers ne sont pas les bienvenus, il faudra d’abord essayer de rencontrer l’évêque de Pskov. » Et pour l’évêque, il me donne cette lettre.

Voilà, donc il fallait trouver, il fallait arriver en Russie, il fallait trouver une ville qui s’appelle Pskov. Il fallait trouver l’évêque. Je suis allé avec mes assistants, Jean Mathieu. C’était le 20 juin ou le 21 juin 2001. Et comment fait-on pour trouver un évêque dans une ville où on ne connaît pas, dans un pays qu’on ne connaît pas beaucoup, on ne parle pas la langue ? Bon, mon système était d’utiliser le réseau des libraires de livres anciens. « Libraire de livres anciens » en russe, ça se dit « bouquiniste », c’est un mot facile qui vient de l’époque de l’occupation russe de Paris en 1814. C’est un des mots qu’ils ont ramené. Alors, j’ai trouvé, j’ai fini par trouver un assez bon livre quand même chez le bouquiniste, et puis là j’ai essayé d’expliquer, je sais pas comment, comment je fais pour rencontrer l’évêque. Et il me signifie avec des gestes, avec quelques mots, que, il a un voisin qui est prêtre, et on va essayer de le trouver. Et on y va, on part, on marche dans les quartiers, et au moment, on s’approche, on voit justement le prêtre qui sort, et le prêtre en lui tend la lettre, il devient très très préoccupé aussi, il s’aperçoit que je ne parle absolument pas russe, il me demande de le suivre. Et il se trouve qu’à Pskov, on était en train de faire une cérémonie pour le 60e anniversaire de l’opération Barbarossa. Et donc sur la colline, il y avait l’évêque, il y avait tout le clergé local orthodoxe, il y avait les chorales de l’armée rouge, il y avait les orchestres, il y avait des milliers d’anciens combattants, il y avait une délégation gigantesque allemande. Et nous, nous étions en short, en tennis, pas prêts pour cette aventure. Mais on m’amène quand même, étant donné l’importance de la lettre écrite par Pierre et son frère Nicolas Apraxine.

Cette lettre était prise tellement au sérieux qu’on m’a amené jusqu’à l’évêque, qui m’a dit : « Installez-vous là, au premier rang. » Et tous ces généraux, anciens prisonniers, me regardaient un peu chagrins, pourquoi ils m’ont demandé, mais qui êtes-vous ? Et je dis, je sais pas quoi répondre, c’était trop long d’expliquer. J’ai simplement dit qu’on représentait Verz, voilà, comme ça on nous a laissé. Nous avons fini par arriver au monastère avec une lettre signée et avec la chevalière, la bague de l’évêque, comme dans les films. La bague, la chevalière.

En apercevant le goumène, le supérieur du monastère, un peu loin, qui était en train de parler au milieu d’une roseraie avec de jeunes séminaristes, j’ai pris mon élan, je suis parti en courant, coursé par différents moines un peu bourrus. J’ai aussi dû sauter une haie. Arrivé, essoufflé, jusqu’à l’île humaine, j’ai tendu ma lettre. Il l’a lue, il l’a regardée, il m’a dévisagé, et aussitôt, ses traits se sont transformés en une autre nature, un peu comme la grèfle blanche devant la noire. Et il est devenu un officier de police parfait en me disant : « Vos papiers. » J’ai tendu mon passeport, et il a vérifié que c’était bien le nom qui était indiqué. Et nous avons été invités à dormir au monastère. Nous avons fini par trouver la clé. Nous avons, voilà, c’est une très longue histoire, nous avons fini par accéder aux cavernes du XVIIe siècle et par découvrir qu’il y avait vraiment un problème dans la description. C’est plus grave, le tombeau ça crée de la famille.

Le sujet était négocié avec un chef mafieux qui cherchait à gagner le paradis pour son âme et qui avait été logé là. Donc cette erreur a été corrigée et quand nous sommes retournés un peu plus tard, on a demandé ce qu’il s’était passé et on nous a répondu simplement que l’inguème, le chef du monastère, était maintenant en train de s’occuper d’un autre monastère, tout en haut, tout au nord de la Sibérie. Voilà là-dessus, donc je vous propose sans plus de transition de regarder. Nous avons Patricia Loconte et Enea Discepoli qui ont préparé un atelier de photographie à travers la boule de cristal, car comme beaucoup d’anciens Russes, Pierre aimait interroger les Augures, les aruspices et les sibylles, les sorcières, avant de prendre un voyage, pour savoir pour quel jour il devait prendre son billet d’avion transatlantique, dans une vieille tradition.

The video is online, here’s the French text and an English translation

Welcome everyone, thank you for coming. Today is May 19, 2023, the second day of meetings for the 3rd Senegalese Photography Biennial. It’s 6:15 p.m. and we’re in the rotunda by the sea. I’m going to hand over to Jean Poderos.

Jean Poderos is a publisher, more specifically a publisher of children’s books and fine books. He has published over 250 books with his publishing house, Éditions Courtes et Longues. For example, he has published a book on Hugo Pratt and a book on the photographer Thiollier in collaboration with the Musée d’Orsay during an exhibition.

I’ll now hand over to Jean. Thank you Serge and good evening everyone. Serge has done it, so I’m not going to introduce myself, but I’m not going to introduce Pierre Apraxine either, who I’m going to talk to you about for a few minutes, and who’s going to reveal himself to you little by little. For those of you who don’t know him, I can tell you that Pierre’s story, my story with Pierre, is the story of an encounter that didn’t happen in 2000. He was organizing an exhibition on the Castiglione at the Musée d’Orsay, and Jean-Michel Ottoniel, the artist Ottoniel, who’s a friend of mine, called me and told me that I was working for your magazines at the time, so I was a journalist, and he said, « Come on, there’s this exhibition, it’ll be interesting for you to meet Pierre Apraxine. » I didn’t go to see Pierre Apraxine, nor did I go to see the exhibition at the Castiglione. I didn’t see that exhibition, which is a great regret today, but that’s the way it is. And then, Pierre, I met him again through another artist friend, Sorbelli, Alberto Sorbelli. You’ll see that Italy is very present in all this. That was in 2005, and I met Pierre on several occasions, notably at dinner parties, where we laughed and chatted. We laughed and chatted, and sometimes curiosity is something that’s sorely lacking, so I didn’t really know what Pierre did for a living. And then, a few years later, I was reading Tolstoy’s « War and Peace », and in « War and Peace », there’s a Count Apraxin. One evening, I was invited back to Sorbelli’s house, and I asked Alberto if Pierre would be there. He said, « Yes, Pierre will be there. So, as soon as I arrive, I throw myself at Pierre Apraxine and say, « Pierre, there’s a Count Apraxine, just like you. » Of course, he doesn’t forget that, and immediately replies, « Yes, but that’s not the branch of my family. » And just like that, he begins to tell me about his life, and to tell it to me through some sort of correspondence, including talking about the places where he lived. And this conversation lasted over an hour and a half. It was a hubbub, as parties often are, but I was completely focused, because he was telling me, and by the incredible story he was weaving for me. At the end of this long conversation, I said to him: « But Pierre, have you ever thought of writing your memoirs? » And Pierre, who was a great man, well, you can’t really see that he’s a great man, but he’s very great, he was always, it was a bit gangly, and then not. And that’s it, sometimes I’m a bit slow, that was it, it must have been in 2015-2016, and it still took me almost three years to constantly turn this idea over in my head, and tell myself that maybe I should suggest that he write his memoirs anyway. Finally, I mentioned it to Jean-Michel Ottoniel and Alberto Sorbelli, and asked them if they thought it would be a good idea. They both said, « It’s an excellent idea, and no one has ever suggested it to him, it’s fantastic, you’ve got to suggest it to him, but he’ll say no. » So, okay, I send him a very short letter, and three weeks later, Pierre replies: « Let’s do it, on the sole condition that I don’t write. » So I had to think of someone who could do it. And Pierre lived in New York, I lived in Paris, so it was a bit complicated. And Automniel, still him, said to me: « Of course, you’re the one who’s doing it, I’d never thought of that solution. » And when he told me that, I said to myself, in fact, he’s right, I’ve got to do it. And Pierre and I organized our first trip. It was in November 2019. Pierre was very tired at the time, hospitalized in a nursing home, and I went to see him. And the first conversation was terrible, because, he told me, « No, no, but we’re never going to do that. » Me, I’d crossed the Atlantic, I was right there for him. And he said to me, « No, no, we’re stopping this, it doesn’t make sense, » in a very, very virulent, almost virulent way, whereas he’s a very gentle man, and I’d always known him to be smiling, funny. And then he got really angry. I call Sorbelli, I say, « Look, here’s the thing, Pierre tells me he doesn’t want to do it. » I wander the streets of New York like this, and then finally, I find a payphone, and I call him, and he says, « No, no, but that’s out of the question, you’re there for that, you call him, you call his assistant, and tomorrow, you go back, you’ll be there at 3pm, and you’ll start working. » That’s what I did, and the next day, everything had changed. There was an incredible break in the weather, and Pierre started talking to me, opening up. So that was the first trip, and then the second trip was in January 2020. And then, you know what happened next, there was the Covid, and so I had to interrupt my travels, and we decided to have telephone conversations once, twice, three times a week, until the borders reopened, and I too, depending on my work, could travel. So I went to see him again in November 2022, and one last time this year, in February, and a week later he passed away.